SEDGWICK, less than a mile from downtown Syracuse, is a neighborhood of tree-lined boulevards, where outsized 1920s Tudor homes with in-ground pools can be had for prices in the low six figures.

Mark Robbins doesn’t live there.

In 2004, when Mr. Robbins, an architect and curator who had been based full- or part-time in New York, Washington or Columbus, Ohio, for most of the previous 20 years, became dean of Syracuse University School of Architecture, he resolved to find a place in the city’s struggling downtown. His goal was not just to find a space to renovate as a showplace for his modernist leanings, or to demonstrate to visiting architects that Syracuse — not exactly a must-stop on the global circuit — might be an inexpensive place to test innovation. His ambition was to help revive, and even remake, the city.

“When I first looked at this job, some people said to me, you’ll only be here three days a week. You’ll go back and forth to New York,†he said. “But what’s the point of that?â€

As dean, he has exhorted his students to make “aesthetically provocative buildings that can change the way a city functions.†And, he added in an interview in March: “The only way you can get that stuff to happen is if people believe you are invested. The only way to get people to believe you are invested is to live here.â€

No previous dean has lived downtown, Mr. Robbins said. Like many upstate areas, Syracuse had been economically hobbled for decades, and the downtown, which was cut off from the surrounding city by Interstate 81 in the 1960s, had deteriorated. Buildings were abandoned, crime rose, and street life all but disappeared. In recent years, according to Matthew J. Driscoll, the city’s mayor, more attention has been paid to the core, and one prominent set of buildings was remodeled as a popular pedestrian shopping and dining area. Still, there was a long way to go. Or, as Mr. Robbins puts it, “The big resource in Syracuse is basically surface parking lots and vacant buildings.â€

No previous dean has lived downtown, Mr. Robbins said. Like many upstate areas, Syracuse had been economically hobbled for decades, and the downtown, which was cut off from the surrounding city by Interstate 81 in the 1960s, had deteriorated. Buildings were abandoned, crime rose, and street life all but disappeared. In recent years, according to Matthew J. Driscoll, the city’s mayor, more attention has been paid to the core, and one prominent set of buildings was remodeled as a popular pedestrian shopping and dining area. Still, there was a long way to go. Or, as Mr. Robbins puts it, “The big resource in Syracuse is basically surface parking lots and vacant buildings.â€

In fact, there was such a surplus of beguiling options that it took him a year to pick a place to remodel. At one point, he considered an empty multistory medical office building from the 1970s that had Mies van der Rohe simplicity. But in the end, he settled on a property that a guide from the university had first shown him when he was undecided about taking the job, offering it as an example of all the great, easy-to-acquire buildings available. “They were smart,†he said. “It really kind of hooked me.â€

An 1898 bank building overlooking a historic square, it had been all but abandoned since 2000, with a bar as its sole remaining tenant. Mr. Robbins bought the whole thing, all 6,400 square feet, complete with its Beaux-Arts limestone facade and a vaulted ceiling running its full length. The building was listed for $300,000, but according to property records, he paid $200,000.

In one way, moving to Syracuse is a homecoming for Mr. Robbins, who is 51 and got his master’s degree in architecture here back in 1981. But Mr. Robbins, a Queens native who still speaks in the rat-a-tat manner of that borough and dresses in slim gray trousers even for tooling around town, feels like a fast-forward character in a real-time town.

He grew up in Floral Park, commuting daily for an hour and half to Music and Art High School, then went to Colgate University. His life changed direction when he got an internship at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, an atelier-style school in Manhattan run by the architect Peter Eisenman, which he remembers as the kind of place where Philip Johnson would drop by and take students to lunch at a local deli. After getting his master’s degree from Syracuse, he worked in New York for a few years as an architect and artist specializing in small constructed objects, then moved on to other activities, including curating architectural exhibitions at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, and directing the design program of the National Endowment of the Arts for a few years during the Clinton administration. He also did larger-scale sculptural installations, and spent a year in Italy in 1997 after winning the Prix de Rome.

When he returned to Syracuse, the challenge, as he saw it, was to hang on to the eclectic point of view he had developed in the two decades since he had been there and still have a practical impact on the city.

He started by holding parties in abandoned warehouses, trying to get local people to reimagine blighted buildings as hidden assets. He moved the school of architecture a mile or so from the campus to a former cold storage complex in a rundown area, and brought in the celebrated minimalist architect Richard Gluckman to renovate it. And he began asserting himself more broadly, pushing the city and the university to recruit high-caliber architects like Toshiko Mori and Julie Eizenberg for other building projects, and not always winning friends in the process.

He started by holding parties in abandoned warehouses, trying to get local people to reimagine blighted buildings as hidden assets. He moved the school of architecture a mile or so from the campus to a former cold storage complex in a rundown area, and brought in the celebrated minimalist architect Richard Gluckman to renovate it. And he began asserting himself more broadly, pushing the city and the university to recruit high-caliber architects like Toshiko Mori and Julie Eizenberg for other building projects, and not always winning friends in the process.

“Developers’ and Mark’s views are quite the opposite, as you might expect,†Mr. Driscoll said diplomatically. The mayor, who deals with Mr. Robbins a lot in his role as senior adviser for architecture and urban initiatives to the chancellor of the university, added that he finds the debates spurred by Mr. Robbins’s efforts “exhilarating.â€

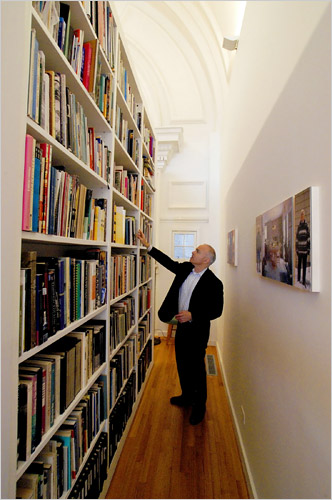

WIDE OPEN The second floor — a 75-by-25-foot rectangle — is divided into an open kitchen, a small private space with a bedroom behind it, and an expansive living area.

On the home front, Mr. Robbins hoped to make his former bank a mixing zone between the worlds — municipal and academic, local and global — that he was trying to bridge. He wanted it to be a place for gatherings where professors, students, policy makers and architects could celebrate architecture and enjoy food, wine and conversation. “It shouldn’t all be sturm und drang; the righteous salvation of an abject place,†he said. “I want it to be a kick.â€

Although the bank’s exterior was always majestic, the inside, when Mr. Robbins first saw it, was office-park gothic. Faux-wood paneled partitions had created a warren-like interior that blocked all light from two great arched windows. The vaulted roof that had originally soared 35 feet above the banking hall — and, in later years, 25 feet above the second-floor addition — had been hidden above a dropped ceiling. Almost all the detailed plaster work had been neatly shaved away.

After ripping everything out and throwing his first party there, he drew up plans, with the help of the New York City firm of Fiedler Marciano Architecture, for a minimalist renovation of the interior. On the ground floor, he built an office, which he rents to other architects; the floor above — a 75-by-25-foot rectangle — he kept for himself. He divided it with a long, narrow kitchen that cuts across the building’s width, creating a small private area with a bedroom, two bathrooms and closets on one side and a ridiculously generous, but stark, expanse of living area on the other.

After ripping everything out and throwing his first party there, he drew up plans, with the help of the New York City firm of Fiedler Marciano Architecture, for a minimalist renovation of the interior. On the ground floor, he built an office, which he rents to other architects; the floor above — a 75-by-25-foot rectangle — he kept for himself. He divided it with a long, narrow kitchen that cuts across the building’s width, creating a small private area with a bedroom, two bathrooms and closets on one side and a ridiculously generous, but stark, expanse of living area on the other.

There is an air of near-institutional restraint throughout, heightened by the whiteness of all the walls and cabinets (Mr. Robbins said the intent was to direct the entire focus of the space toward the ceiling), and by a relatively tight renovation budget, which, given the size of the building, meant that high-end materials were kept to a minimum.

Aside from the white Carrara marble counters in the kitchen and the oak floorboards (used to prevent warping from the radiant heat), there is little that speaks of luxury. Nevertheless, he ended up spending about twice as much as he had on buying the building.

The sheer size of the living area can be startling, an effect that was not lost on Mr. Robbins as the project progressed. “A month before the construction was complete I was up here and I had a panic,†he said. “I thought, I am going to feel like an outtake of some Hollywood movie. It is going to be me with a bottle of brandy dropping on the floor at 3 a.m., because it felt so grand and so theatrical.â€

He says that he is over that now, and that the place, modestly but warmly furnished with vintage modern and contemporary pieces, feels like home. But the moment it comes out, the statement sounds like equal parts wishfulness and truth. Mr. Robbins maintains a small one-bedroom on Gramercy Park. Unable to find suitable work in central New York, his partner of 10 years, Brett Seamans, the director of marketing at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, lives there, and the two take turns commuting on weekends — a situation Mr. Robbins acknowledges is far from ideal.

But Mr. Robbins says he does take satisfaction in the fact that he has been able to start building his own society around him. He throws large parties only infrequently, but has had sit-down dinners for more than 70 people a couple of times a year, and has smaller, less formal gatherings at least monthly. Since he moved here, he said, several new faculty members, many of whom had previously been living in large cities, have moved downtown as well.

Paul Michael Pelken, an assistant professor at the school of architecture, moved from London in 2007. “It’s been quite a change from London, and having lived in major cities for a long time,†he said in an e-mail, adding, “I rent a loft-style apartment that would be hard to afford in London or New York.â€

Kevin Lair, who left an architecture practice in Boston to join Syracuse as an assistant professor last fall, recently bought a 6,300-square-foot former bottling factory about 10 blocks north of Mr. Robbins for $165,000.

He said it was the prospect of taking part in the transformation of Syracuse that pulled him in. During his interview with Mr. Robbins, he realized that they shared a vision of melding academic thought with practical application.

“When I toured during my job interview, the main thing that stood out was the relationship of the school of architecture to the community,†Mr. Lair said.