When it comes to life decisions, Clive McCarthy doesn’t shy away from grand leaps. The British-born electrical engineer was near the peak of a long career in Silicon Valley, where he directed chip and software design for the semiconductor company Altera, when he went in an entirely new direction.

In 1997, around the time he turned 51, he took a few years off and then enrolled in art school. Then he began staging public performances with live avant-garde music and teams of painters who executed the large images he envisioned, and later he started devising art-producing algorithms, using TVs and computer monitors as dynamic “canvases” for his work.

He also began dating Tricia Bell, a physician. In 2005, four months into their courtship, Mr. McCarthy showed her blueprints for his future home and studio in the San Francisco’s Mission district. When Dr. Bell, now 59, asked about a space labeled “Tricia’s Room,” he explained, “It’s a room you can transform however you please.” And if she ever became peeved with him, he told her, “it can be your little retreat.”

It was a bold move so early in their relationship. But, he recalled, “I was already certain how I felt about Tricia, and I needed to make my intentions known.”

Dr. Bell, who is now his wife, was charmed.

The gritty fringe neighborhood where he had bought a 10,000-square-foot structure wasn’t where he had first planned to settle, but his efforts to build a contemporary home on upscale Russian Hill had met opposition. So when he unexpectedly found this 1925 concrete building amid auto body shops, he took the leap, buying it for $2.3 million.

Originally a Lucky Strike cigarette warehouse, it had also been the home of Capp Street Project, an organization known for its experimental art installations in the basilica-like main hall, a vast concrete room rising 24 feet to a pitched skylighted roof. Ann Hamilton once blanketed the floor there with 750,000 honey-dipped pennies, Bill Viola installed an indoor redwood forest and Carl Cheng flooded the room like a swimming pool.

The next owner had carved up the space, though, so Mr. McCarthy was unaware of the building’s art world provenance. But Stanley Saitowitz, the designer he hired to renovate it, remembered the warehouse from its Capp Street days and set about reclaiming it as a place for making art.

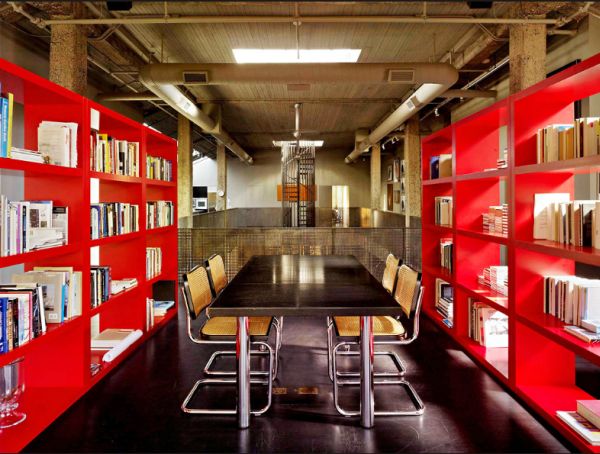

“Clive gave us a pretty open canvas,” Mr. Saitowitz said. “We wanted to create emptiness: a playground for his experiments, for all the different things he works on simultaneously.” The idea was to restore the openness and rawness of the space by peeling away dropped ceilings, paneling and partitions, and then to insert into that rough setting “little jewels or set pieces,” he said, meaning discrete rooms or objects with greater refinement and intimacy.

Now, where redwoods once soared, a spiral stairway encased in steel rods rises to a roof garden. Mr. McCarthy’s studio takes center stage in the big central space, where his “Electric Paintings” morph and regenerate on skeletal screens. One level up, on the original perimeter mezzanine, Mr. Saitowitz created pockets of domesticity, like a huge master bath lined in pristine white tile with a rain feature. In the open kitchen, a 39-foot silvery granite work island doubles as a dining table.

Dr. Bell said she has never needed to retreat, peeved, into “Tricia’s Room,” but she has transformed it with a green wall like the one in the bedroom that recalls Mr. Viola’s redwoods.

Meanwhile, the creative spirit of the building’s earlier days has spontaneously seeped back. Artist friends gather for group critiques, and when the couple invites avant-garde ensembles to rehearse or perform, the whole place resonates with music.