05 Feb

Tribeca is one of those neighborhoods in New York City whose names indicate a history of change. Like SoHo, it takes its contrived, relatively newfound label from the geography of its borders—in this case, the loose “triangle below Canal†defined by that street to the north and by Broadway and the Hudson River on the long sides. Like SoHo, too—or Noho, Nolita, Dumbo and all the rest—the name was devised to mark the shift of the neighborhood away from industry and toward finer pursuits – especially art, shopping, living.

In the case of Tribeca, the posh area of lofts and lattes that has arisen there over the last 20 years first coexisted with and then replaced the Washington Market, the city’s wholesale larder. When the last of the egg-and-cheese dealers left Duane Street a few years ago, that phase of the neighborhood’s life was definitively put to rest. But the built residue it left—the loading docks that line the Belgian-block-paved streets, the arch-punctured fortress warehouses in brick and stone—are still calling all the designerly shots.

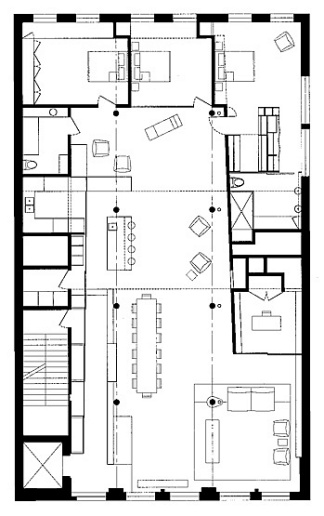

The – since sold – home of movie director John Curran and Kristen Frederickson, longtime Tribecans from a few blocks away, is a perfect statement about the area’s reinhabitation. The 80-foot-deep three-bedroom loft apartment was designed by New York’s Ike Kligerman Barkley Architects, with Joel Barkley taking the lead. It manages to celebrate the guts of the old neighborhood without any denial that there is much to enjoy about the new.

Before - A 12-inch-thick concrete floor had to be removed with a jackhammer. “It looked like the world’s largest collection of moon rocks,†Kligerman says.

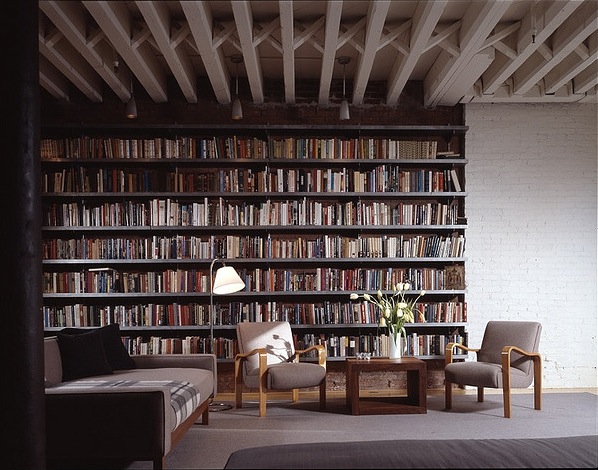

After. The living area has a felt rug and vintage Thonet Industries armchairs. Wool felt sofa fabric from Decorators Walk.

Before it was elevated to its present state, the second floor of this brick-fronted, cast-iron-boned building on an overlooked side street was used for decades as a butter warehouse. Then, during a brief interregnum in which the area was colonized as a down-market outpost of the nearby Wall Street business district, it served as an office for an insurance broker. It was at that time that the space suffered the indignity that would be the renovation’s principal challenge to correct: the pouring of a 12-inch-deep concrete floor on top of the original wood one. It was duly jackhammered out at the start of construction—“We called it Beirut on the Hudson,†Frederickson says—a move that won back the space’s original 11-foot ceilings but presented, as these things always do, a new cascade of problems. Chief among these was the elevator, the primary entrance, which had been installed to meet the former height.

Before. Barkley’s goal was to create “an open, dramatic, dynamic construction that also held room for the warm, soft, comfortable, cozy.â€

After. A large raw space was turned into a combined dining area, kitchen and living area. Beyond the 1955 Danish teak table hang plaster relief figures by Brenna Beirne. The flooring is “green†bamboo. “In 13 months you could grow what you’d need to replace it,†Kligerman says.

Barkley and his clients—for whom he had previously designed a summer house in New Jersey, never built—arrived at a simple solution that recalls the evolution of the space. “It’s kind of a sitcom entry, like on The Mary Tyler Moore Show,†the architect says. Stepping out of the elevator, you find yourself on a mock-concrete platform from which you can survey the L-shaped loft space at the heart of the apartment.

The living area, in the short leg of the L, is straight ahead, defined by a custom bench and sofa and a pair of vintage Thonet Industries armchairs (the firm’s Mia Jung collaborated on the interior design) and lined with floor-to-ceiling zinc shelves that continue into the study, which lies beyond. (The bookshelves have made such an impression on their daughter’s friends—her room, which is tucked into the opposite corner of the apartment, includes a wall-long stage complete with curtains—that they have gone home and reported to their parents that “Avery lives in a library.â€) The living area is prevented from appearing to float too much in the space by its thick felt rug and by one of the loft’s handsome ornamented columns, which comes down to anchor one corner.

The effect of so much of this bright, fine-grained fiber is to divorce the new construction from the vestiges of the old—the columns, the deep beams that span the spaces, the exposed-brick walls (both painted and plain) and the braced joists that support the floor above.

In the master bedroom, an 18th-century English oak chest sits before the original brick-and-stone wall. Above the bed are black-and-white photos taken of the figures in the living area.

There is also a kind of practical wit in evidence here that serves to synchronize the design with the ethic of the neighborhood—and to deflate pretension. For instance, where that column in the living area comes to ground, an ellipse has been cut through the rug; zippers radiating from it at the cardinal points provide a touch of ornamental detail, anchor the plain yet commodious furnishings and—not least—allowed the thing to lie around the column in the first place. Downlights in the one dropped ceiling—necessary to hide the ventilation ducts and pipes of the apartment above—are scattered without pattern in what Barkley calls a “constellation.†From the master bedroom, a window at pillow level gives a view out onto the living area. (In one wall there is a low portal that lets the cats, one friendly, three retiring, get to their hidden backstage loo.)

The kitchen has bamboo cabinets and stainless-steel counters, shelves and backsplashes. Screens, left, help divide the area. Viking range and hood.

In the kitchen, there is a glass-front refrigerator—Frederickson, an art historian who owns a gallery nearby, says that “curating†the exposed comestibles is her secret obsession—and a large porcelain sink that strikes one of the few off notes in this carefully conceived home.

“All I wanted was a white farmhouse sink and a place for my books,†Frederickson explains. Her husband also got his own design hiccup approved: The door to the master bedroom, which continues up a few feet past the rest, breaks a datum that is established by the honeycomb-filled plastic panel walls and reinforced in the hanging of two series art pieces. That this request was granted to Curran, a financier on the tallish side, speaks volumes about the useful lack of ideology that drove Barkley’s design process and that gives the apartment such an unpretentious feel. “It was my birthday present,†Curran says, smiling.

A ceramic-tile bench and a stainless-steel towel bar in the master bath are bisected by the frameless glass shower wall. Randomly placed downlights echo similar ones elsewhere in the loft.

The smile is well deserved. When he first saw the derelict floor of the aging building that would become the family’s home, he says he thought to himself, “Let’s just leave now. This is never going to happen.†Barkley counters with a more positive spin: “It was just a blank canvas.†But Frederickson, who knows a thing or two about that particular metaphor, gets the last word. “No,†she says. “It was a horrible, dirty, disgusting canvas.â€

Pingback: Tribeca Citizen | In the News: Dutch Pavilion